Understanding any changes in behaviour:

What has happened can have a significant impact on your child’s behaviour. Depending on your child’s age and the methods the offender used, they may have some questions around sex and relationships. If you are unsure what to say, take time to seek advice from professionals but always start with what the child knows. Answer their questions as clearly as possible. You know your child and their level of understating so make it relevant to them.

Trauma Response:

Trauma response is the term given to describe the reaction we may have to something harmful or frightening. You may see your child acting in a way that to you is confusing. This may be your child’s trauma response.

The main parts of the brain that are involved in a trauma response are the Pre-frontal cortex, the Hippocampus, and the Amygdala.

The Pre-frontal cortex is the part of the brain behind your forehead. It is responsible for regulating emotions and is often not fully formed until early adulthood. When faced with a threat the pre-frontal cortex effectively goes offline. This impairs the ability to control emotions and responses. You may shout, cry, or even laugh inappropriately. You may struggle to find the right words or articulate what you want to say.

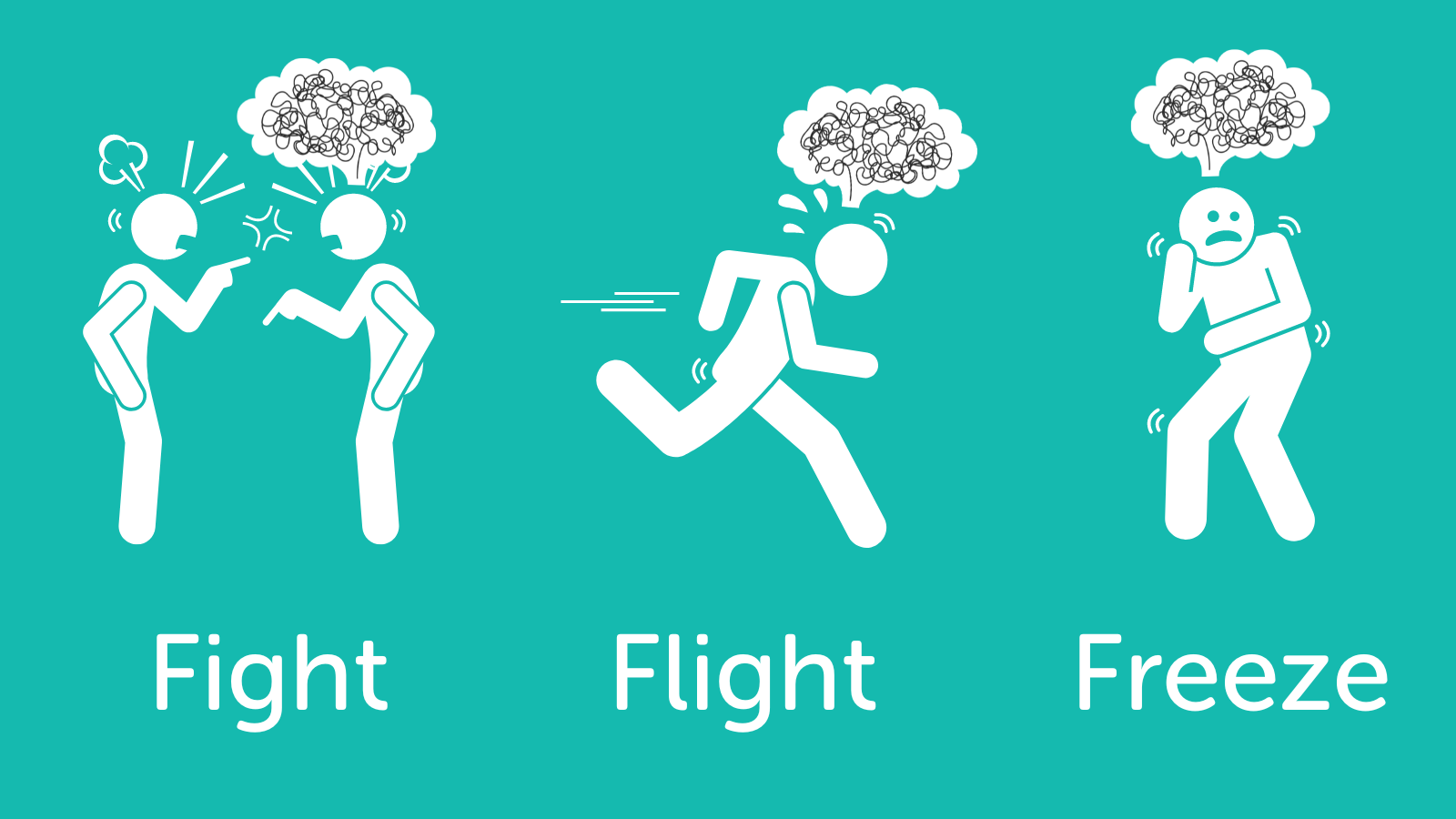

The Hippocampus is the part of the brain that process memories and groups them. An example is certain smells reminding us of a childhood memory. This is the Hippocampus grouping that smell with that memory or experience. Following trauma this means there is a risk that similar smells and/or sounds may trigger a trauma response and any point in the future. Trauma can also lead to memories not being ‘recorded’ in order or in detail so your child may not be able to recall events as you would expect them to. Check out this useful video on the fight, flight, freeze response.

.png?ver=aQKYaqUTEsEF2gQWJNt4Mg%3d%3d)

The Amygdala is the brains warning alarm. Most of the time it is not responding but is always alert to the fact you could be in danger. When it senses danger, it responds by releasing a chemical in the brain that triggers a set of physical reactions. These are explained as fight, flight, freeze, flop or fawn. Fight is when you attack the perceived risk, flight, when you run away from it, freeze when you cannot move away from it, flop is when you do not resist, and fawn is befriending the perceived risk as a way to lessen the impact or stop it. When the perceived threat is no more, the person will often feel very tired.

The best way to understand how this works is to think about your reaction when the police visited. You were probably experiencing a traumatic response.

Did you feel overwhelmed with the information being told and wish you had asked more questions afterwards? Did you get upset, shout, cry, etc. and struggle to ask specific questions, often repeating the same phrase or question? This could be the pre-frontal cortex being affected.

Did you struggle to remember everything that was said? Were you annoyed that you couldn’t recall certain details? You may recall clearly what was playing on the radio or TV; or that the officer was in plain clothes and what they were wearing. This may have been because your hippocampus was not remembering detail in order and was therefore only capturing fragments.

You may have been aware of your heart beating faster or having sweaty hands. Your stomach may have felt funny, and your legs might have been shaking. These are all responses caused by the amygdala getting you ready to respond and what you were feeling was the blood being pumped to different muscles to aid in any fight, flight or freeze.

It is important to recognise the behaviours you may be witnessing as a biological response and not deliberate ‘bad behaviour’. An example is a child who pushes a teacher out of the way and runs out of the school. It is not necessarily about wanting to harm the teacher or run away. They may have been triggered and their amygdala response was flight meaning they ran and would push away anything in their path.

If your child is struggling with trauma and/or anxiety speak to your GP about support. Ask your school to complete a risk assessment so they know how best to support your child. For some children, therapy can really help them understand why they feel the way they do and help them develop strategies about what to do when they get these feelings. In the children’s section a therapist has provided some strategies that your child may use.

Talking to your child:

In the children’s resource we give advice to them about how to talk to you and what might make it easier to have the discussion with you. For a lot of children having a conversation that doesn’t involve sitting opposite you or making eye contact can be easier. Things like going for a walk, a drive or helping you cook will give an opportunity to talk without it feeling so intimidating. If your child senses you are struggling to manage the conversation they may not talk as they don’t want to upset you. Explain to your child that even though it all may feel difficult you are here for them and ready to listen if they want to talk.

On our website we have a full resource that goes into more detail about this topic. But briefly, here is some information you may find useful at this time.

We recommend the CARES approach to support you in having difficult conversations.

Calm, non-judgemental listening. Fake it if you have to! Make it clear you don’t blame them. Take deep breaths, pause to give yourself space. Keep them talking while you gather your thoughts with phrases like “I see” and “Tell me a bit more.”

Ask open questions and assess – give them time and avoid asking “Why?” as this feels like an accusation and a judgement. You can’t change what has happened, so asking why they did something just gets you caught in a loop of blame and recrimination. However, you can rephrase a ‘why’ question to be less accusing and more open, so instead of “Why did you do that?” you could try “What led to that happening?” or “When/how did it start?”. Agencies may also be talking to your child so a conversation with them may help you understand a little more about what as happened.

Reassure and give information and support. Reassurance does NOT mean saying it will all be ok – but it does tell them that this is just a moment in time. There will be life after this. Reflect back their feelings and acknowledge how hard it must be. Take care not to trivialise here – you’re not aiming for a “Come on, get over it” any more than a “This is a disaster!” You want to strike a happy medium where you acknowledge the hurt and pain while giving hope that recovery is possible and there are steps to be taken to move forwards.

Enter their model of reality and imagine how this feels for them. They may be talking to you, but this doesn’t mean they are entirely sure that what happened was wrong. They may feel guilt and shame as well as defensiveness and desperation. There are likely to be conflicts and doubts. If they have been groomed online, they may still have an emotional connection to the perpetrator. However difficult that is for us to accept, it’s vital that we acknowledge it. Reassure them that you know this is difficult and complex for them emotionally.

Seek support and self-care. Don’t blame yourself; contact relevant professionals for advice. Don’t worry if your child would rather talk to someone else – this is another opportunity to signpost them to support. You have not failed and responsibility for the harm rests absolutely with the perpetrator. Continue an open and accepting dialogue with your child and re-establish safety. Avoid treating your child as different because of the abuse and find ways to be a family unit again, without reference to the abuse.

Remember, you are not to blame yourself. It is not your fault. Your child will probably have the same feelings that ‘if only I had…’ or ‘I shouldn’t have’. It is important that the actions that have caused the harm and distress are on the offender not you or your child. This can be difficult to do but it is important that you remember it was someone’s actions that harmed your child and the blame lies with them.

Victim blaming must always be challenged and comments from any professional who attributes blame to you and/or your child should be challenged. This shows a lack of understanding about this type of abuse and is poor and harmful practice.

Wider support:

School/college

Talk to your child about who may be able to support them in their school/college. It may be helpful to speak to the safeguarding lead or head teacher. Some schools will have pastoral support and they can be there for your child. They may be able to do some support work with them if they need it. It is also worth checking if there are assemblies or classes that will be focusing on this issue to enable your child to decide if they feel able to be part of them or not.

Childrens Social Care

The police must notify children’s social care if they have concerns that a child has suffered any type of abuse. Children’s social care should contact you to let you know they have received information that your child has been harmed and to see if there is any support that they can provide you. It may be that your child is receiving support from somewhere else and children’s social care is not needed.

Children’s social care may want to meet with you and your child to explore further how they can support you to keep your child safe. If this happens, make sure they are clear with you about what support they are offering, what they will be doing and for how long. It is good to be clear about what can and cannot be provided. An example is therapeutic support - in a lot of areas this will need to be accessed through your GP or local charities.

GP/Health

If the abuse has impacted on your child’s physical or mental health speak to your GP. They can discuss any medical options or strategies to help your child. It may be appropriate for your GP to make a referral to Children and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) who are specialists in this area.

Victim Support

The police may ask you if you want to be contacted by a victim support organisation. This is often a phone call from a service that may be able to offer some practical advice that will help you through this difficult time.